Spaghetti and Twine

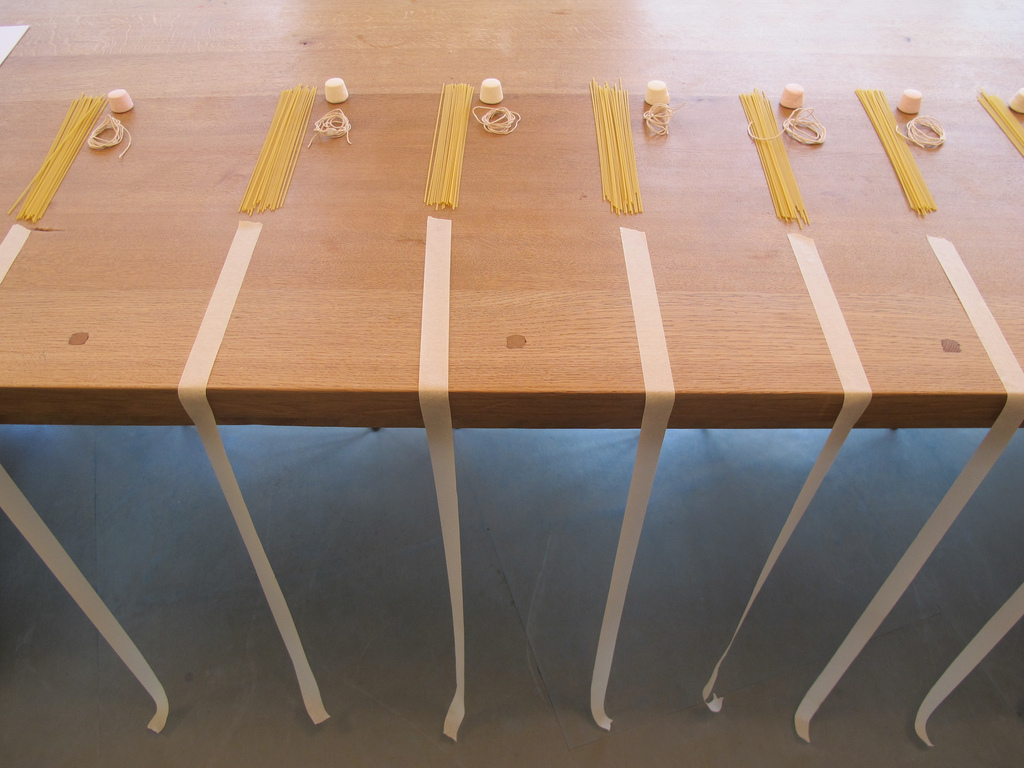

Many of you will be familiar with Peter Skillman’s Marshmallow Challenge, an exercise frequently given to teams and business school students. Teams of four are given 20 pieces of spaghetti, 1 yard of tape, one yard of twine, and a marshmallow. They are then given 18 minutes to build a free-standing structure that places the marshmallow as high off of the table as possible. The team with the highest marshmallow wins.

If you haven’t seen it already, Tom Wujec’s TED talk is a good place to learn about the challenge. And if you haven’t introduced your team(s) to it, take 45 minutes out of one of your days to administer the challenge and see what revelations you get.

In his talk, Wujec introduces three points that he hopes teams will get out of taking the challenge.

- Prototyping matters.

- Diverse skills matter.

- Incentives magnify outcomes.

Anyone intimately familiar with Agile software development methodologies are likely to nod their heads in agreement, particularly with the first two points. For folks in the Waterfall world of thinking, this experience is often the first step to opening their eyes. Indeed, one of my colleagues exclaimed, “The customer is the marshmallow!” And with this, I knew that we had a bit of an opportunity to convert a few more folks to our way of thinking…

Triumphant Marshmallow

To illustrate his first point, Wujec points to teams of business school and kindergarten students. The business school students spend a lot of time orienting themselves to the task and planning. They then build a nice, tall structure sans marshmallow. At the last moment before time is called, a team member ceremoniously places the marshmallow on the top of the spaghetti tower and… plop. The tower collapses or falls over and the team is left with a sad pile of spaghetti.

Kindergarten students focus on the marshmallow. Rather than adding the marshmallow at the last moment, they often include it as part of their iterative designs. They build slowly and test often.

The parallels to software development could not be more clear. Does your team often spend weeks or months planning some grand new product enhancement, only to watch it flop with customers at release?

Indeed, this reflects a certain degree of arrogance on the part of the product manager. He might claim, “I know exactly what I am doing. I’ve listened to the customers and I can design a big feature/application/product that will delight our customers and create value.” I see this most with new startups, particularly those run by folks who aren’t particularly familiar with software development. They get a great idea for a product, shop it around a little, and engage with an engineering shop. Since they’re thinking of this as a “job” with a finite ending rather than an ongoing process, they write up some big plan together and begin development. If the founders are lucky, they’ll wind up with a product that resembles their initial grand vision. Only if the founders are extraordinarily lucky, however, will they wind up with a a product that actually meets the needs of their users and earns revenue.

So my advice for teams engaging in software development—particularly new founders engaging with 3rd-party development shops—is this: remember the mantra “The customer is the marshmallow.” It’s all well and good to get some grand vision of what your product will be. But leave it at that. Your most important task is to identify the minimum “shippable” set of features and get that out in front of your customers as soon as possible. And listen to them. Two good things could happen:

- With any luck, the minimum set of features you decided to ship also included a way for you to delight customers, create value, and—depending on your ethos—do good in the world. Chances are, you did this in 3 months rather than the 12 months it would have taken for you to build your grand vision. Delighting customers gets you word-of-mouth advertising, creating value gets you money, and doing good in the world often gets you both. All of this makes it much more likely that you’ll survive another 9 months.

- You’ll learn something. If you ship it and it flops, you’ll learn something. If you ship it and it blows up, you’ll learn something. If you ship it and it’s an unexpected success, you’ll learn something. So long as someone is using it and you’re looking at the numbers and paying attention, you’ll learn something. Chances are, you’ll change what you had in mind for the rest of your product.

“The marshmallow is heavier than we thought.”

You might not have heard these exact words at a product release, but you’ll might hear phrases such as “the application can’t handle the load,” “we didn’t think of this edge case and it really hurts us,” or “nobody is using our product.” Wouldn’t you rather hear that earlier?

At the end of the day, most systems are relatively complex. Some are more complex than others, but few can be completely understood on paper. It takes time spent within and looking at a functioning system to understand how it actually operates. There are often dozens of edge-cases that work their way out of the woodwork. Defer planning and specification to the latest possible moment; everything you learn in the meantime will make your product better.

All of this requires a degree of comfort with uncertainty. It’s not clear where your product will be in 12 months. It’s also not always clear how long it will take to release Feature X. The alternative, however, isn’t any rosier. The waterfall method makes you think you know what your product should look like. You think you know exactly when your product will ship. Neither of these are true unless a) you are unwilling to change your product based on customer feedback or b) your developers added so much padding to the schedule that you do ship “on time.”

Personally, I’d rather embrace ambiguity. Ship quickly and often. Acknowledge what you don’t know. Instead of trying to “nail things down,” defer commitment and specification until you’re almost ready to begin development. However, there is no excuse for intellectual laziness. Your goal isn’t to fail, but to do whatever you were going to do quickly enough so that you have enough data to make smart decisions.

One of my favorite videos is Mary Poppendieck’s “The Tyrrany of ‘The Plan.’” It is one of the most elegant arguments for an iterative development process that focuses on the organization’s combined capacity rather than attempting to run a balanced system, being realistic and pacing work at the organization’s capacity, and working together to build further capacity. Those familiar with Eliyahu Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints (first introduced in his book “The Goal“) will find themselves nodding in agreement and hopefully connecting their findings to their own software development organization.

The TED Talk was delivered in 2010 by Tom Wujec. He only mentioned Paul Skillman who had invented this chalenge. But I haven’t found any track of Skillmans talk at TED.

Olga, you’re absolutely right. When I looked at the TED talk again, it was in fact Tom Wujec who delivered it. The text indicated that Peter Skillman talked about it at TED, but it could have been a hallway conversation for all we know. Thanks for the correction! 🙂

Can this be played with teams of 2?

Ooh, interesting! I don’t see why not. The group dynamics would be different but I think it’d still get the point across. If you try it, let us know what happens?

[…] cet exercice est analysé pour le monde du service client ? suivez ce lien (lien en anglais : http://chrisgagne.com/926/the-customer-is-the-marshmallow/ […]