What a 106-year-old psychological law tells us about stress in the office

Work harder!

We’ve all been admonished to work harder at some point in our lives, whether it was from a well-meaning parent, a sports coach, or a manager facing a deadline.

What many Agilists have come to empirically observe is that the more we can get people to feel happy and have a good work/life balance, their total productivity goes up. We’ve come to learn that “busyness” is not productivity. I have heard managers brag of how dedicated their teams are because they’re working 100-hour weeks on their latest and greatest innovation. Yet, they seem miss out on the fact that had their teams spent 35–40 hours a week on their latest and greatest innovation, it would be less late and even greater.

So, why do some managers insist upon added stress and arousal? Clearly there must have been a time or place where “cracking the whip” made sense.

Hint: It’s not in highly creative fields like software development.

It turns out that there are some times when it makes sense. According to the Yerkes-Dodson law, an “empirical relationship between [physiological and mental] arousal and performance,” performance increases when arousal does but only up to a point. In some cases, further arousal lowers performance.

For simple tasks, more arousal equals more performance, at least up to a point at which it relatively plateaus. For difficult tasks, more arousal equals more performance, until it reaches a peak and begins to plummet at the rate that it rose. This is because stress negatively affects cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and problem solving, all critical for the modern knowledge worker.

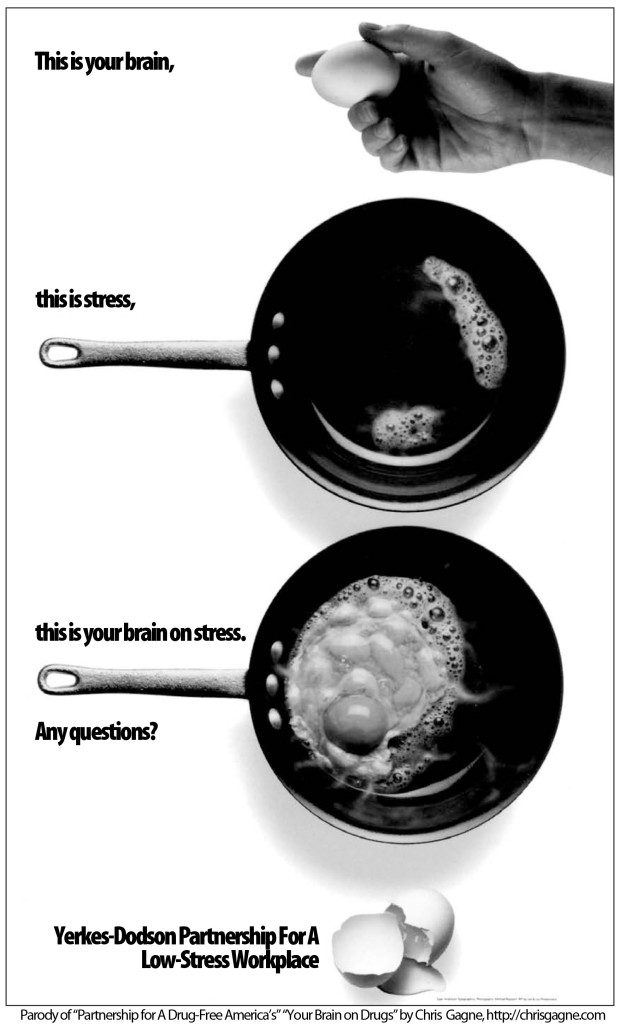

Put another way…

One of the things that I really like about Agile is that it’s all about staying empirical… Transparency benefits inspection, inspection benefits adaptation. And over the years, we’ve come to learn in the business context what many have learned in the psychology and biology contexts.

For instance, a 2007 review of the effects of stress hormones like glucocorticoids found that people’s performance on memory tests and the levels of stress hormones in their blood produced very similar responses to what Yerkes and Dodson found nearly a century earlier. One example: the ability to form long-term memories was highest in the face of small quantity of glucocorticoids were in the bloodstream, but removing the adrenal glands (thus no glucocorticoids) or injected glucocorticoids produced poor long-term memory formations.

Interestingly, this same review found that in order for something to induce a stress response, it has to be perceived as: novel, unpredictable, uncontrollable, and/or possibly leading to social rejection. Naturally, any knowledge worker’s office is likely to be plagued by novelty, unpredictability, and a lack of control (at least from external circumstances like competition).

One of the things Agile teaches is is how to manage these constants well. Rather than stressing out and feeling like we need to “replan” because “things didn’t go the way we planned,” Agile assumes that things won’t go as planned. Uncertainty is embraced. Servant leaders who understand the nature of software development reality deeply understand these things, and so don’t unnecessarily create a culture of fear that produces the sense of a “social evaluative threat” when “the plan isn’t met.” The plan hypothesis was wrong in the first place.

Thus, workers in strong Agile cultures are more productive not only because they aren’t working 80-hour weeks, but also because the whole culture (especially the leadership) is mature enough not to freak out at every single change. These workers experience less stress, therefore they’re producing less stress hormones, and therefore their brain isn’t acting like it’s about to be eaten by a tiger. Keep in mind the tiny amount of time that has elapsed between the constant fear of violent death and the modern 72°F office environment, at least from an evolutionary perspective.

This is your brain on stress.

Truly Agile companies then put A+ talent in environments where they feel autonomy, mastery, and purpose, thus providing strong intrinsic motivation (which does not cause the same sort of stress). A+ talent will not tolerate an environment of mediocrity, fear, or command and control, so any such talent in such an environment exits post haste. This leaves behind giant teams of B and C players who send the company into a tragically-slow death spiral from which few can escape. Further, small teams of A+-level absolutely run circles around giant teams of B- and C-level talent (kudos to Steve Jobs for popularizing this). Many people have never seen this in action.

It’s easy to feel like a hero or a martyr when you’re working those eighty-hour weeks “for a cause.” Managers can tell their employees that they’re not “strong enough” and need to “man up” and put in the hours. But try as we might to ignore them, rarely can we escape the simple facts of our physiology and biology.

Thanks to Wikipedia for illuminating me on the Yerkes-Dodson law, from whose article I borrowed liberally for my own.